SwitchDin is a Newcastle-based energy technology startup aiming to crack open the enormous potential of distributed energy resources (like small-scale solar and battery storage) in Australia’s energy future. The company enables virtual power plants (VPPs) and microgrids by creating a common language for different brands of products (inverters, batteries, etc) and then managing those assets to meet a range of energy goals – all while bringing a monitoring & control platform to end users.

How the small stuff fits into the big picture

Let’s start with the big picture. Australia is currently is in the throes of an energy revolution. This transition has two main facets: Large-scale renewables like solar & wind farms (plus more recently ‘big batteries’), and small-scale, distributed renewable energy resources (DERs) like rooftop solar & home battery storage.

Both are similar in that they come with challenges and opportunities, but the small-scale side of things is arguably more interesting in the way that it disrupts the status quo. For the first time, an increasingly large part of our electricity generation infrastructure is paid for and owned by private citizens & small businesses instead of government or industry. There are now nearly 2 million solar electric systems (or 3 million small-scale systems altogether) with a total generating capacity somewhere in the region of seven gigawatts (7GW).

Right now, these distributed resources primarily serve to benefit their owners, who are generally motivated by self-interest – including both the financial benefits and the warm, fuzzy feelings associated with generating clean energy. With the advent of affordable solar and (increasingly) battery storage, households and businesses are able to meet a portion (or less frequently – all) of their energy needs on-site, with their excess energy (usually solar) automatically being fed into the electricity grid.

Compare Solar & Battery Quotes

The end result is this: Rather than become assets that have been systematically and methodically integrated into Australia’s electricity infrastructure, deployment has happened in an ad hoc manner, and small-scale systems are underutilised. For this reason, Enphase co-founder Raghu Belur once described them as ‘barnacles on the grid‘. While this description is a bit uncharitable (distributed solar has already had a massive, positive impact on Australia’s energy infrastructure) it manages to capture the essence of the problem: Distributed energy resources are capable of doing more.

The end result is this: Rather than become assets that have been systematically and methodically integrated into Australia’s electricity infrastructure, deployment has happened in an ad hoc manner, and small-scale systems are underutilised. For this reason, Enphase co-founder Raghu Belur once described them as ‘barnacles on the grid‘. While this description is a bit uncharitable (distributed solar has already had a massive, positive impact on Australia’s energy infrastructure) it manages to capture the essence of the problem: Distributed energy resources are capable of doing more.

This is unfortunate not only for Australia’s electricity grid, but also for system owners themselves. If they’re going to be connected to the grid anyway, they may as well put their systems to optimal use for our infrastructure as a whole – and get paid accordingly for the contribution that they make. This is particularly important if they’ve got batteries, which hold enormous promise for the grid.

Managing distributed energy resources

In the emerging energy system, it’s no longer just a matter of pumping electrons from a small number of large generators (like coal, gas & hydro plants) to their points of use. Instead, there will be a constant balancing act that will need to occur between numerous points of generation, storage and consumption – many of which are all three at the same time. Layer on the complexities of dealing with the intermittency associated with wind & solar, and it becomes abundantly clear that the system will need ‘smarts’ to keep that balance.

Key to those smarts is the ability for all the individual components to communicate with each other via a central information hub – the brain that coordinates the whole system. It is the job of this system overseer to preside over this data and ensure that every moving part (including batteries, inverters, DREDs and perhaps even human residents) behave optimally – for both reasons of efficiency (putting each resource to best use) and stability (preventing blackouts). This is referred to as ‘firming’ a renewable energy supply, and it’s becoming increasingly important as renewable energy resources come to the fore.

The problem of managing DERs on the main grid (the National Electricity Market, NEM) is not a pressing issue at this point in time. The NEM is stable and has plenty of redundancy built in with large generators, so the underutilisation of small-scale resources is more a matter of missed opportunity and indicative of lack of future adaptability.

By contrast, in fringe-of-grid, microgrid and off-grid situations there is already growing opportunity for renewable energy firming – with more and more people and organisations looking for cost-effective alternatives to expensive diesel generators and/or network infrastructure upgrades. These situations are usually viewed as crucibles for DER management technologies, as they are more resource-constrained and unforgiving than the primary grid.

Software, hardware & integration

In essence, there are two problems to address when it comes to optimising distributed resources in an energy system. The first is the software algorithms that understand the data and issue the directives telling the hardware what to do, while the second is the hardware itself.

Some companies develop the two together as a package, meaning that their products essentially exist and operate in their own sphere, to the exclusion of other companies’ products. You can call this the Apple model – and in the solar & storage space, Tesla is the biggest example. Others focus primarily on software, while still others put their energy into making the hardware.

System integrators, meanwhile, are another class of companies that develop hardware and/or software that facilitates inter-device functionality and communication – even if the hardware components are made by different companies.

Babel fish (with a brain) for distributed energy

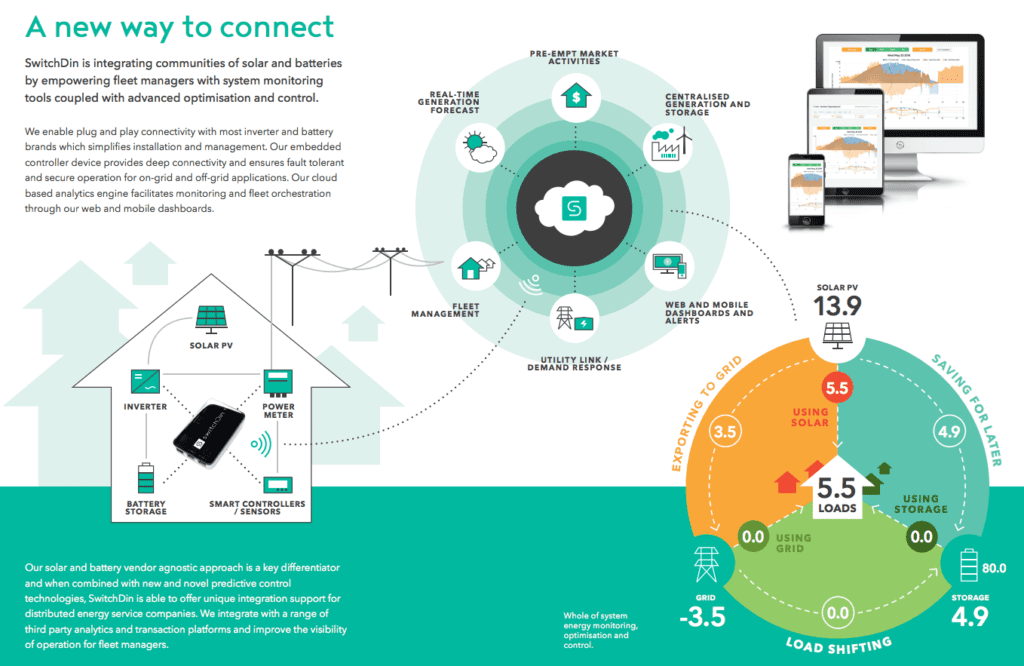

Integration is what SwitchDin sees as its key differentiator. The company has developed integration technology that will work with the vast majority of commonly used components (mainly inverters & batteries) in Australia – having created what is in effect a babel fish for distributed energy systems: its Droplet controller (which also serves as an on-site EMS). Going a step further, it also has the algorithmic intelligence to manage them all: its Stormcloud cloud platform.

Interestingly, it’s the algorithms that came first. SwitchDin was established with the aim of solving the problem of optimising distributed resources in an energy system, and the company’s original goal was to create smart control software that would do just that. But founder Dr Andrew Mears soon realised that designing the algorithms only solved part of the problem; software was only useful if there was a way to apply it across the wide range of products available (and already deployed) across Australia. Depending on the manufacturer, each of these may speak different languages, so getting them to ‘play nice’ with one another often proves difficult or impossible without integration. This meant that irrespective of the sophistication of their software, it would have limited applicability.

This spurred the company to look at the the next piece of the puzzle: Making sure that its technology would work directly with all of the most popular product brands in the country. The size of this task was not to be underestimated (and was apparently very fiddly), but the rewards for developing something simple and streamlined would be vast – both for the SwitchDin as a company as well as for Australia’s rapidly transforming energy sector.

The resultant hardware is the company’s ‘Droplet’: A small, internet-connected device (or embedded software) that optimises the performance of that individual system, but also serves as a ‘virtual inverter’ that speaks to and is managed by Stormcloud. StormCloud’s algorithms optimise performance for fleets of Droplet-equipped DERs, ensuring that they perform in accordance with set preferences, within prescribed constraints (e.g. network import & export limits) and in order to maximise overall system efficiency. It can even learn from past trends to plan for the future with the weather forecast in mind. These features make SwitchDin an ideal Virtual Power Plant (VPP) enabler and microgrid manager.

In short, SwitchDin enables the smart, distributed grid of the (fast-approaching) future by making distributed resources more useful – not only for individuals but also the electricity system as a whole.

The age of distributed energy: Where SwitchDin fits in

More and more, companies all over Australia are looking for or developing technologies that aim to harness the power of distributed energy resources. There are now several commercial VPP programs available to households and businesses with the the right equipment – namely, batteries and a smart EMS. Regional electricity networks (such as Ergon in Queensland and Horizon Power in Western Australia) also looking at ways to improve energy system reliability by putting their distributed resources to more effective use; these networks are microcosms of the NEM and a glimpse into the future of Australia’s energy system. As a sign of things to come, Victoria and South Australia have recently introduced battery incentive programs that have a VPP-ready eligibility requirement.

How SwitchDin works – overview (Click to enlarge)

SwitchDin is aiming to grow into one of the major players in the rapidly evolving distributed energy management space. The company’s technology is already used in projects in Queensland, Western Australia and Victoria – including several commercial microgrid projects, a stability & efficiency optimisation project for WA’s Horizon Power, and a batteries-for-diesel replacement project at the Lockhart River remote community in QLD – among others. SwitchDin also works directly with equipment manufacturers, integrating with a range of inverters, batteries and metering equipment to help build the grid of the future.

SwitchDin is actively seeking new opportunities in partners to grow their prominence in the system integration & microgrid spheres, putting itself forward as a vendor-agnostic, VPP-enabling platform for solar installers & retailers as well as a problem solver for situations with serious constraint issues.

Compare Solar & Battery Quotes

- Solar Power Wagga Wagga, NSW – Compare outputs, returns and installers - 13 March, 2025

- Monocrystalline vs Polycrystalline Solar Panels: Busting Myths - 11 November, 2024

- Solar Hot Water System: Everything You Need to Know - 27 February, 2024