The Canberra Times recently published a piece about the concerns about potential glare from the solar panels of the proposed 4 megawatt (MW) Mount Majura Solar Farm, given its proximity to Canberra Airport. This article addresses concerns about glare from solar panels in aviation and examines a number of similar case studies both internationally and elsewhere in Australia.

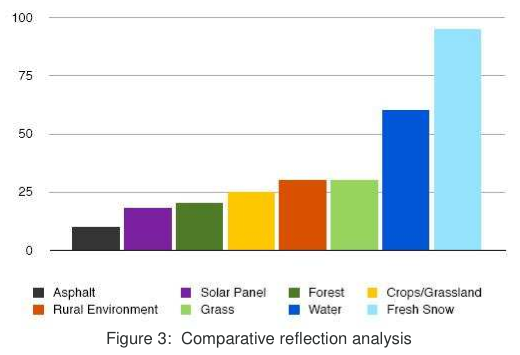

1. Solar panels are designed to absorb light, and accordingly reflect only reflect a small amount of the sunlight that falls on them compared to most other everyday objects. Most notably, solar panels reflect significantly less light than flat water.

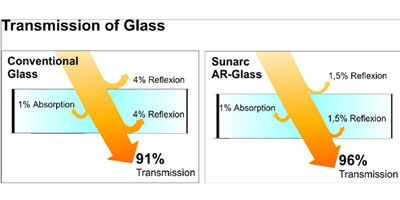

In fact, glass, one of the uppermost and important components of a solar panel, reflects only a small portion of the light that falls on it–about 2-4%, depending on whether it has undergone an anti-reflective treatment. These days, to increase solar panel efficiency and power output, most panels are treated with some kind of anti-reflective coating. Below is an example of how Sunarc’s antireflective technology–just one available on the market–can increase light transmission in glass and reduce reflection.

(Image via Sunarc.)

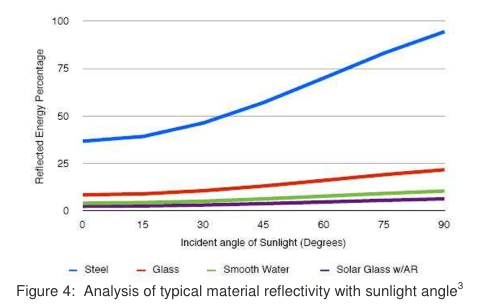

The chart below compares the reflectivity of smooth surfaces at different angles of sunlight. Solar panels treated with antireflective coating reflect a lower percentage of light than smooth water. Steel, a common building material, reflects far more incident sunlight than either.

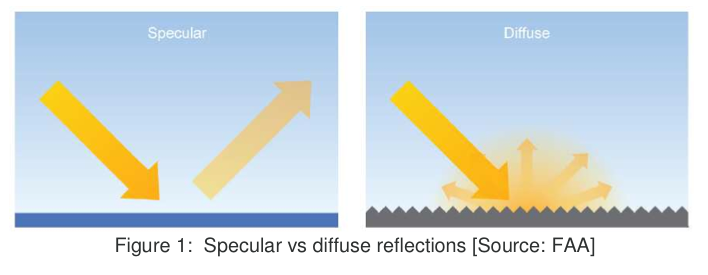

2. Of course, it may not seem fair to compare the quality of light reflected from grass to that reflected off of water or glass. Smooth surfaces such as glass and still water exhibit ‘specular reflection‘. This is when light hits the surface at one angle and ‘bounces off’ in another direction, much like a mirror. Specular reflection can be contrasted with ‘diffuse reflection’, which occurs when light reflects off of microscopically rough surfaces and scatters. Diffuse reflection is what happens when light hits virtually everything in our field of vision.

When the sun is reflected on a smooth surface, it can result in glint (a quick reflection) or glare (a longer reflection) for those who are on the ‘receiving’ angle. In both cases the light reflected is diminished by having first hit the substrate that reflected it–unless that surface is a perfect mirror. When the sun is the original source of the light reflected off a reflective surface, the time and position at which glare or glint might occur depends on the original position of the sun in the sky in relation to the location of the viewer.

When the sun is reflected on a smooth surface, it can result in glint (a quick reflection) or glare (a longer reflection) for those who are on the ‘receiving’ angle. In both cases the light reflected is diminished by having first hit the substrate that reflected it–unless that surface is a perfect mirror. When the sun is the original source of the light reflected off a reflective surface, the time and position at which glare or glint might occur depends on the original position of the sun in the sky in relation to the location of the viewer.

Pilots are familiar with this sort of reflection, usually from bodies of water (which, as noted above, has a higher level of reflectivity than glass or solar panels). Airports are commonly found in close proximity to lakes and the ocean (Sydney’s Kingsford Smith being one such case).

3. The biggest glare hazard in aviation is the sun itself–particularly when it is low on the horizon. In an international, comprehensive analysis of potential glare hazards (pdf – see section 7) in aviation from solar panels, the UK’s Spaven Consulting points out that a trawl of UK and US aviation incident databases between the years 2000 and 2010 for accidents in which glare was cited as a factor reveals that in the overwhelming majority of these cases, the source of the glare was the sun itself. The handful of other cases were mainly related to glare from water on the tarmac or from a nearby body of water. In no case was glare from solar panels or ‘similar facilities’ cited as a contributing factor to an accident.

4. Numerous airports around the world have solar installations located on their premises. Among those in Australia that have installed large arrays are Adelaide Airport, Alice Springs Airport, Newman Airport (WA), and Ballarat Airport. Internationally, solar arrays have been installed at or near airports in Singapore’s Changi Airport, London’s Gatwick Airport, California’s San Jose Airport, Germany’s Dusseldorf Airport, the US’s Denver International Airport, Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada, and Ontario’s Thunder Bay Airport, to name a few. The preponderance of examples in which solar panels have been installed at, on or near airports is testament to fact that they are not automatically a hazard to pilots.

Particularly noteworthy and a close analogue to the Majura Solar Farm with regard to its position in relation to an airport is the Indiana Solar Farm. 2MW of solar panels facing due south are located under 1km south-west of runways. Stephen Barrett of US consultancy HMMH, which has undertaken glare assessments of numerous solar installations at or near airports across the US–including Indianapolis Airport–said that the majority of projects that HMMH had been involved in were developed by the airports themselves and were therefore careful to adhere to FAA guidance. He also noted that the FAA only requires glare assessments for developments that occur within 2 miles (about 3.22km) of touch-down.

The Indiana Solar Farm, less than 1km southwest of the landing strip at Indianapolis International Airport. (Photo by Alex Dierkman.)

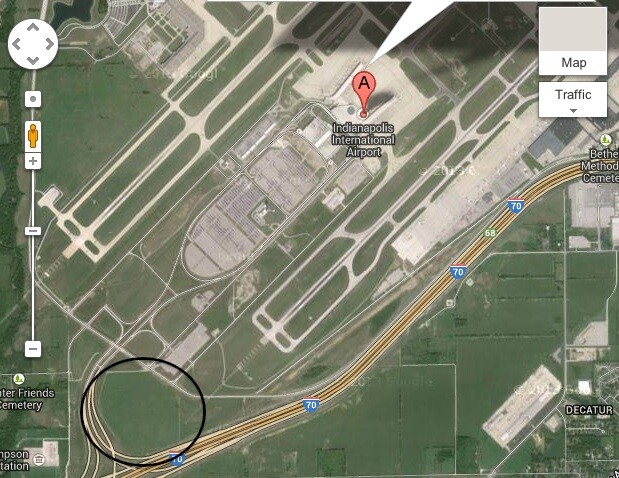

The location (circled) of the Indiana Solar Farm in relation to Indianapolis Airport runways. Panels are not visible because the map is out of date. (Image via Google Maps.)

Dusseldorf International Airport, Germany (Image via AvaiationPros.)

Denver International Airport , Colorado, USA (Image via Worldwater & Solar.)

Nellis Air Force Base in Nevada, USA (Image via Nellis Air Force Base.)

The 8.5MW Thunder Bay Airport Solar Park (Image via Recharge News.)

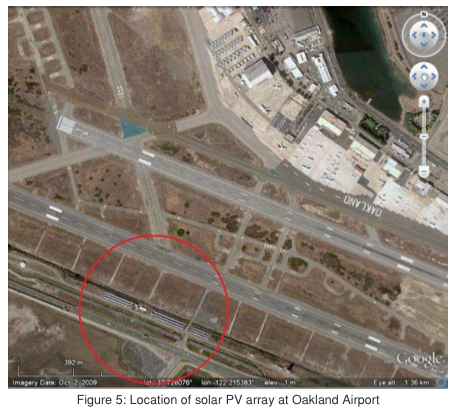

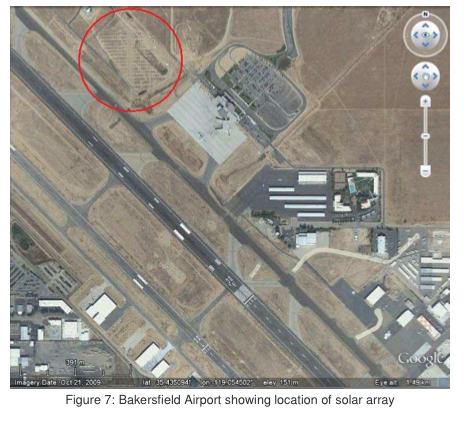

Two Californian airports specifically noted in Spaven Consulting’s report–Bakersfield and Oakland–have solar arrays directly adjacent to the tarmac or even between runways (images below). Both of these arrays underwent analysis during the planning process to ensure that glare was not an issue, and neither has reported complaints about glare from pilots since the arrays were installed.

5. The Spaven Consulting report notes that because of their low reflectivity solar developments ‘en route’ to an airport (but not actually located on the premises of an airport) are unlikely to warrant a glare analysis. In the event that such an analysis is deemed necessary, the above points (about the low reflectivity of panels) are should be taken into account. The Mount Majura Solar Farm will be located 7km north of the airport, making it unlikely that pilots flying in and out will experience any interference due to reflection of light from the panels. Furthermore, because the nose of a commercial aircraft is tilted slightly upwards prior to landing, should any light be reflected off the panels during a landing, it is more likely to fall on the underside of the plane than shine into its cockpit.

Further reading: Spaven Consulting’s report on reflectivity & glare with solar panels (pdf)

Images via Spaven Consulting

© 2013 Solar Choice Pty Ltd

Can I ask about Figure 4? It looks wrong; as the angle of incidence approaches 90 degrees, for example, the percent of light reflected from glass gets very near 100%, not 25%. This is well known. Look: http://research.vuse.vanderbilt.edu/bmeoptics/bme285/mainframes/module3/module3pics/m3pic26.jpg

I realize this article was posted years ago…

Any law suit about solar PV reflection?

Hi Chew,

Not as far as we’re aware.

This interests me a lot – just yesterday I received a notice from the ACT Government (Environment Department) that a complaint about “Environmental Nuisance” caused by solar reflection has been received and now I need to address. IS there a similar article to the above that focuses on household reflections ?

M

Hi Mat,

At this point there is not, but we will let you know if we put something together on the topic. To date it hasn’t proved to be a concern among our readers.