Since its launch in December, the Tesla big battery, formally known as the Hornsdale Power Reserve, has mostly been performing a mixture of tests, trials and just a little showboating.

The latter has included going from zero to 100MW in 140 milliseconds, jumping in ahead of contracted generators to arrest falls in frequency as big coal generators tripped off-line, and just generally being smart and fast.

But last week, in the midst of the heatwave and the gyrations in supply, the battery showed it had moved on from that phase, and on to the business of demonstrating its ability to cash in and make money for its owners.

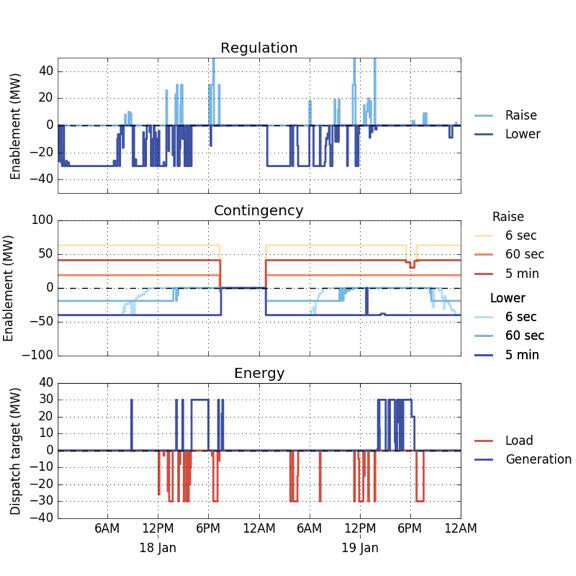

This was particularly visible in the price spikes that hit the South Australia market on Thursday and Friday, with its periods of generation occurring mostly during times of high prices, and charging, or load, coinciding with lower priced periods.

The advantage of the Tesla big battery over other sorts of storage, and particularly over fossil fuel generation, is its ability to switch on and off in an instant, meaning it is capable of responding immediately to change in demands and pricing.

The Hornsdale operator uses around 30MW/90MWh in the wholesale market as a form of price arbitrage, balancing wind output from the neighbouring Hornsdale wind farms, taking advantage of spikes and dips, generating when supply gets tight, and making micro adjustments to supply and demand.

The rest of the battery – around 70MW, 39MWh – is contracted by the South Australia government specifically to deliver “network” services, such as frequency control at a time of system faults and problems.

These three graphs above – from McConnell at the Climate and Energy College, and sourced from NEM data – are a good illustration of how the battery can divide its services between several different needs. So far, the battery has pleased its owners (and developers), and has exceeded expectations.

Compare Solar & Battery Quotes