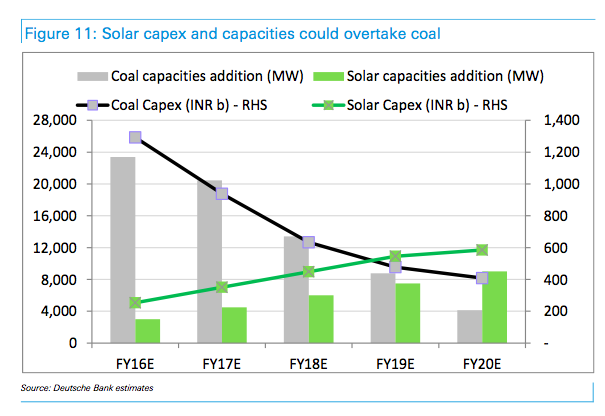

According to Deutsche, which has described Indian government forecasts for solar as too optimistic, by its own estimates of 35GW of solar by 2020, this causes an 8 per cent cut in the volume of coal burned for generation, rather than an increase as most analysts expect.

This, in turn, would hit the most expensive coal hardest, reducing volumes by the equivalent of 70 million tonnes, or around one-third of current coal imports.

That would save India about $US17 billion a year. But it would be devastating to the Abbott government’s hopes of expanding the Australian thermal coal export industry, particularly in the Galilee Basin. The demand is simply not there, particularly with imports from China also falling by one half.

And while Deutsche Bank questions whether the Indian government can deliver on its lofty targets of 100GW of solar and 175GW of renewable energy by 2022, it does not contest the economics.

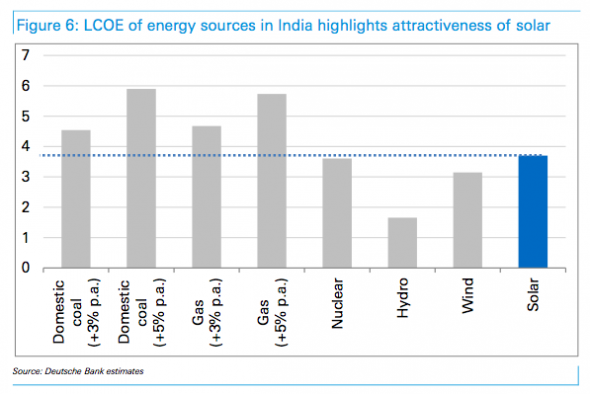

It notes that while solar may look more expensive than thermal generation on up front costs, over the life cycle (no fuel costs), it is already competing with coal. This graph below shows it is already cheaper on a levelled cost of energy basis than domestic coal. Coal generation with imported coal is even more expensive.

This has been borne out in recent tenders for both solar and coal-fired generation. An auction of 300MW of solar capacity in the state of Madhya Pradesh attracted numerous bids of just above 5 rupees – these included from SkyPower and from majors such as Reliance Power, Adani Power, MK, Welspun, Sun Edison and two public sector companies.

“Looking at the tariffs discovered in recent bids for solar and coal, the parity is almost there for buyers,” Deutsche Bank noted.

“Importantly, with increase in coal prices, solar could look cheaper in next few years.” And it is important to note that the bids were fixed for solar, but rising with inflation for coal.

© 2015 Solar Choice Pty Ltd