In the emerging new energy landscape, the idea that a large number of households could quit the grid altogether, using rooftop solar and battery storage, is still considered an unlikely scenario.

But a new report out of Hong Kong suggests grid defection may not be the economically radical idea that some, and particularly the Australian networks lobby group, like to say it is.

The analysis, by Charles Yonts from broking firm CLSA, is based on the example of three different Australian families to show just how balanced the equation – of staying on the grid or leaving it – might be.

In his scenario, Yonts uses an average household consumption of 7,000kWh a year, and flat pricing through the day of US20c/kWh. (Some of his figures may be confusing to Australian readers because he uses US currency).

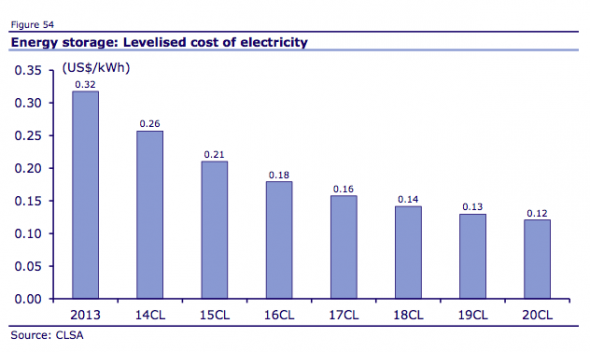

He assumes that the levellised cost of energy for solar is US$0.10/kWh and the levellised cost of storage is US$0.21/kWh. (He predicts it to fall much further by 2020, see graph below).

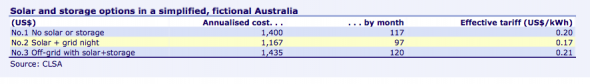

Here are his scenarios:

Family No.1 simply buys all its electricity from the grid, for a monthly bill of about US$117, with effective tariff of US$0.20/kWh.

Family No.2 gets one-third of its power from solar and consumes all solar power it produces (good for illustrative purposes; in actuality, quite difficult since most of the family would likely be gone during peak production midday). The remainder is purchased from the grid at the regular cost. The monthly costs (P&L) are US$97, or effective tariff of US$0.17/kWh.

Family No.3 goes off the grid entirely. All of the power they consume comes initially from solar, with an upsized solar installation feeding into the battery bank for consumption in the evening. In addition to producing 7,000kWh each year, the family has to pay for 3,500kWh of storage (or roughly 10kWh per day). The monthly costs work out to around US$120, with an effective tariff of US$0.21/kWh.

“The ideal economic option for our fictional Australian family, assuming they have access to equity and credit, would be to install solar panels and use the grid as a giant battery, saving around US$20/month,” Yonts says.

But, he notes, if the Australian utilities were to put in place an additional network charge for solar households of more than $US20/month and assuming tariffs are expected to be stable, then it no longer makes sense to install panels.

But this changes very quickly if: solar panel installation costs fall even marginally (as Yonts expects they will); battery installation costs fall – even marginally – (as Yonts expect they will – see graph above); tariffs rise (as expected); or the “homeowner was willing to sacrifice US$3/month to tell the utility to get stuffed.”

“We suspect all four of these are likely, with cost reductions for both solar and storage almost inevitable.” As Yonts notes, this explains the “panicky” proposal by the energy networks lobby for compulsory grid tariffs for all – even though they do not use it – or allowing the networks to load their costs up front, in fear of grid defection later.

© 2015 Solar Choice Pty Ltd